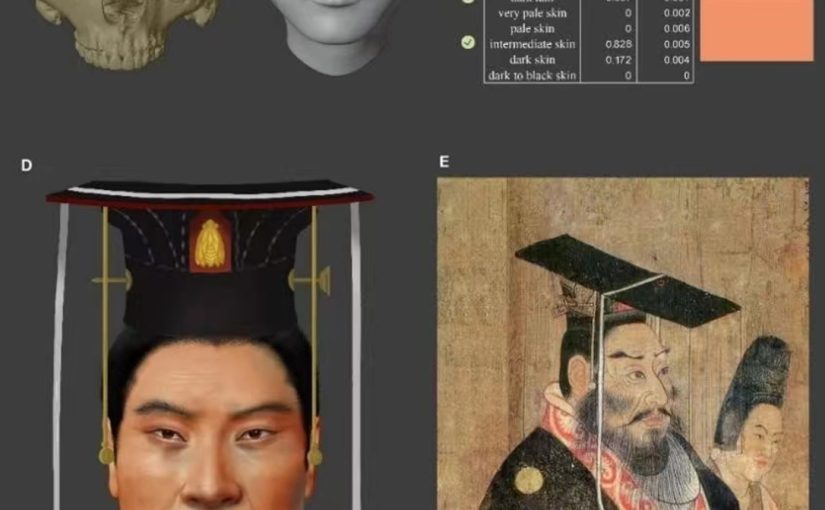

The computer-reconstructed image of Emperor Wu (lower left). Photo: Courtesy of Wen Shaoqing

Wearing a royal crown, with black hair set against yellow skin and brown eyes, the figure embodies the typical appearance of a North or East Asia native. On March 28, the appearance of Emperor Wu of the Xianbei-led Northern Zhou Dynasty (557-581), a Chinese emperor from an ethnic minority group who lived in the sixth century, was unveiled. This marks the first time that the appearance of an ancient emperor has been reconstructed using technological and archaeological methods.

Emperor Wu (543-578), also known as Yuwen Yong, belonged to the Xianbei nomadic group, which originated from the Mongolian Plateau. He was an ambitious leader who reformed the system of regional troops, pacified the Turks, and unified the northern part of the country before his death at the young age of 36.

Recent achievements by a team of Chinese scientists have granted us a glimpse into the visage of the ruler from about 1,500 years ago, shedding light on both his physical appearance and the potential reasons for his death – a stoke or chronic arsenic poisoning due to long-term use of elixirs, which were believed by ancient people to bestow eternal life.

The emperor’s reconstructed face shows that he had dark black hair, yellow skin, and brown eyes, in line with the phenotypes of present-day East or Northeast Asians. This is different from what some people had imagined the Xianbei people looked like.

More importantly, “this study found direct evidence of the integration between the Xianbei nomadic group and Han group among the nobility during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386-589) period and the formation of a unified multi-ethnic country through ethnic integration in ancient China,” Wen Shaoqing, an associate professor at the Institute of Archaeological Science at Fudan University and leader of the research team, told the Global Times.

A member of Wen’s team scans Emperor Wu’s limb bones. Photo: Courtesy of Wen Shaoqing

From remains to profile

Obtaining intact skeletal remains and high-quality genomic data have proven to be the foremost challenges in reconstructing the appearance of ancient Chinese emperors in the past. Luckily, excavations from 1994 to 1995 in Northwest China’s Shaanxi Province unearthed skeletal remains including the skull and limb bones from the tomb of Emperor Wu.

However, the genetic material extracted from the skeletal samples was of poor quality due to environmental pollution, said Wen. In 2023, the research team extracted over one million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of his DNA after employing new research methods.

Over the course of six years, the research team has determined that Emperor Wu possessed a typical East or Northeast Asian appearance by analyzing pigmentation-relevant SNPs and conducting cranial CT-based facial reconstruction

For a long time, the appearance of the Xianbei people had been a controversial topic, with some historical records indicating that the group had characteristic thick beards, yellow hair, and protuberant noses. Other historical records suggested that there was no difference in appearance between the Xianbei people and other people in Northeast Asia. “Our findings are more in line with the second viewpoint,” Wen stated.

The study has also brought to light the reasons behind the premature death of Yuwen Yong as pathogenic SNPs suggest he faced an increased susceptibility to certain diseases, such as stroke.

Through the analysis of 33 trace elements in the remains of the emperor, the levels of arsenic, boron, and antimony in his body were significantly higher than the average levels among contemporary commoners and nobility.

Additionally, on Wu’s femur bone, the research team discovered a spot of black discoloration, which “may have been caused by localized bone marrow necrosis from arsenic poisoning-inducing skin lesions,” according to Wen.

It is documented that during the period in which Yuwen Yong lived, the upper echelons of society revered the consumption of Daoist elixirs for spiritual enlightenment and longevity. These elixirs contained substantial amounts of arsenic, boron, antimony, and other trace elements.

Historical records indicate that between 575-578, Emperor Yuwen Yong fell ill multiple times, predominantly featuring skin diseases. The research team believes that the emperor’s death is consistent with the pathological manifestations of chronic arsenic poisoning.

Bring history to life

According to Wen, the research team analyzed Emperor Wu’s genome, revealing the ancestry of the Xianbei Emperor and his family from a genetic perspective. It was found that Emperor Wu not only shared the closest genetic relationship with ancient Khitan and Heishui Mohe samples as well as modern Daur and Mongolian populations, but also showed additional affinity with Yellow River farmers.

“Our study has revealed genetic diversities among available ancient Xianbei individuals from different regions. The formation of the Xianbei group was probably a dynamic process influenced by admixture with surrounding populations,” Wen noted.

The latest research sheds light on what the research team has been engaged in, “systematically tracing the lineage and relationships between ancient populations by analyzing skeletal remains unearthed from archaeological cultures in different periods and regions to describe the dynamic process of ethnic fusion within the Chinese nation.”

For example, the Hexi Corridor has long served as a vital route for the exchange of populations between the East and the West. However, due to the scarcity of ancient DNA data, research into the region’s population history has been nearly nonexistent. Through the reconstruction of ancient genomes, the genetic history of populations in the Hexi Corridor has been illuminated, confirming the profound impact of major historical events on its people.

According to Wen, in modern times, molecular archaeology also plays an important role in the identification of martyrs’ DNA, family reunification efforts, and facial reconstructions.

Currently, the team has analyzed over 2,000 samples from prehistoric and historical periods, and more than 1,500 samples from martyrs. However, there is still a long way to go before reaching the final goal.

“Molecular archaeology can bring history back to life, with the only challenge now being the ability to obtain high-quality genomic data of ancient people,” said Wen.